Introduction

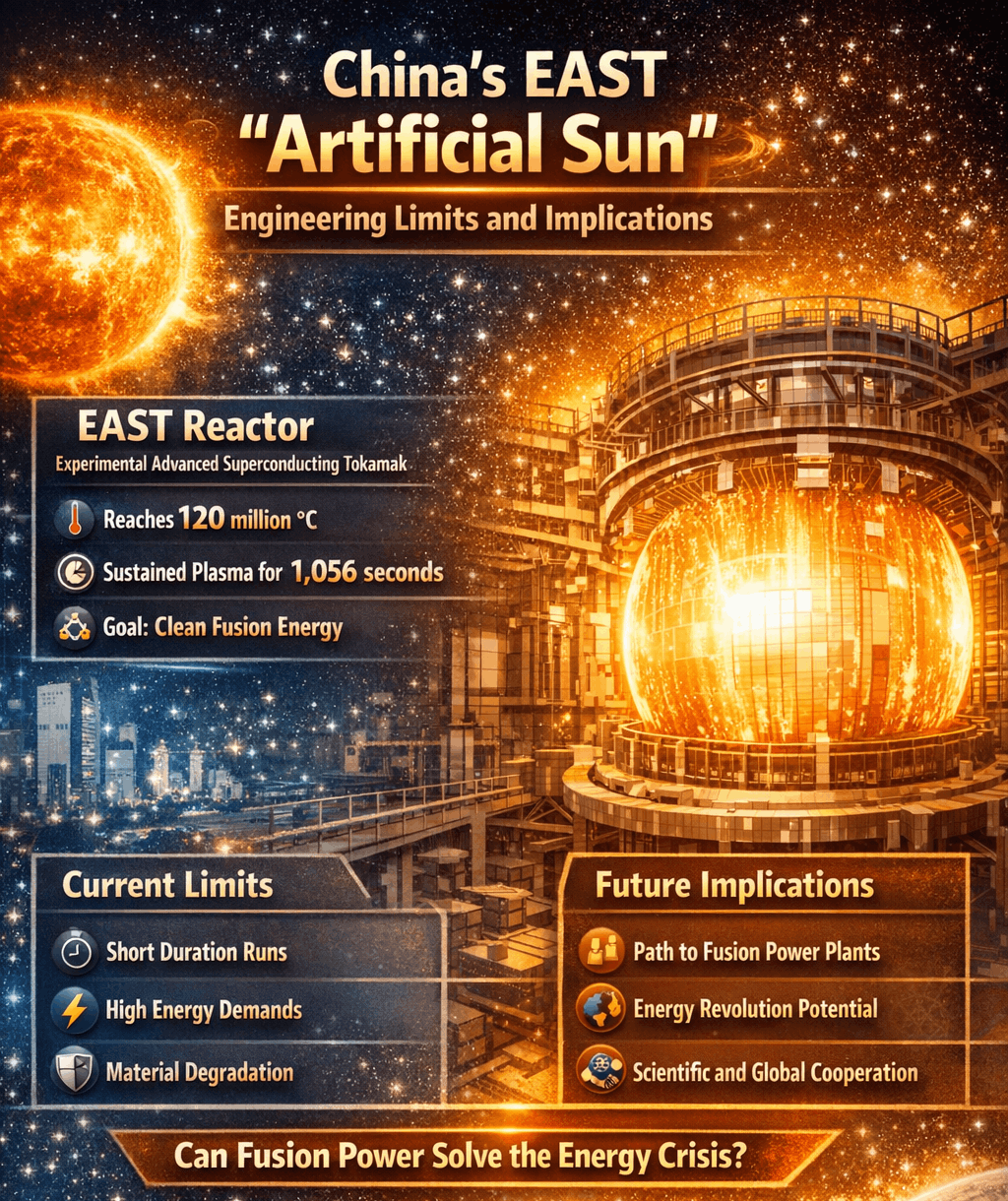

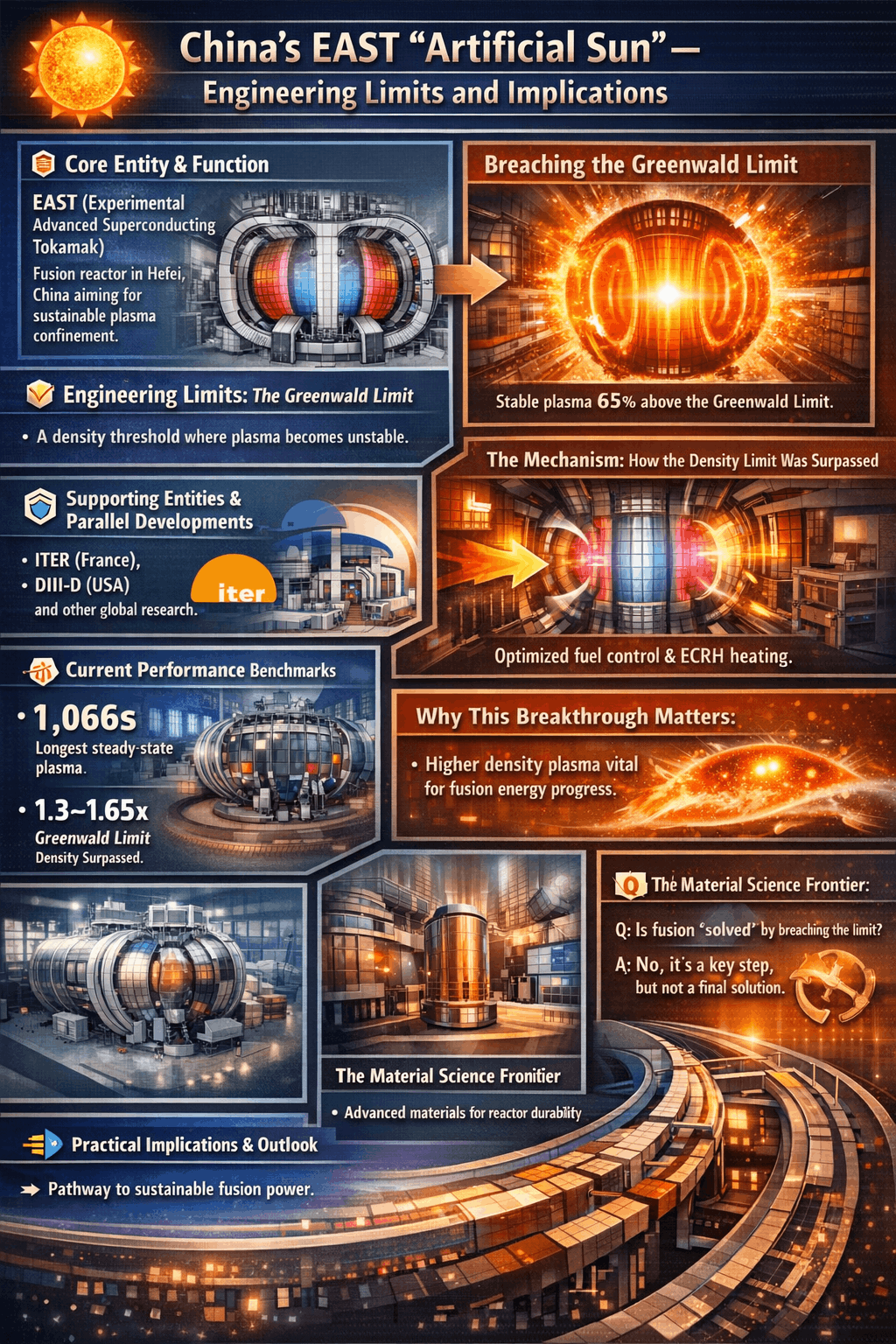

China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST), known as the “Artificial Sun,” is a magnetic fusion reactor designed to replicate the energy of the Sun by confining plasma heated above 100 million °C. Its goal is to unlock practical, near-limitless clean energy Operated by the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science since 2006; this device is engineered to replicate the Sun’s energy-producing fusion reactions on Earth. In a major breakthrough, EAST scientists surpassed the long-standing Greenwald limit, once thought to cap stable plasma density.

In the global race for clean energy, China’s Artificial Sun represents a decisive shift from theoretical fusion science to real-world possibility. This Artificial Sun, known as the EAST fusion reactor, has demonstrated that long-standing limits on plasma stability can be overcome through advanced engineering rather than accepted as fundamental barriers. By breaking the Greenwald density limit and sustaining ultra-hot plasma, the Artificial Sun signals a future where fusion power could be smaller, more efficient, and capable of delivering near-limitless clean energy to the world.

Core Entity and Function

Primary Entity: The Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) is a magnetic confinement fusion reactor located in Hefei, China.

Core Function: It is designed to contain and study ultra-hot plasma—an ionized gas—within a donut-shaped (toroidal) chamber using powerful superconducting magnets.

Research Role: EAST acts as a critical testbed for technologies destined for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), the multinational fusion megaproject in France.

Recent Technical Milestone: Breaching the Greenwald Limit

The Barrier: For decades, the Greenwald Limit was considered a hard operational ceiling for plasma density in tokamaks. Exceeding it typically causes destructive instability.

The Achievement: In January 2026, EAST researchers reported sustaining stable plasma at densities 1.3 to 1.65 times the Greenwald limit.

Key Innovation: This was achieved not by brute force, but by precisely engineering the plasma’s interaction with the reactor wall during start-up, validating the Plasma-Wall Self-Organization (PWSO) theory.

The Mechanism: How the Density Limit Was Surpassed

Controlled Start-Up: Scientists carefully managed the initial fuel gas pressure and applied Electron Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ECRH)—a method using microwaves—at the beginning of each plasma discharge.

Impurity Reduction: This technique minimized the sputtering of metal impurities from the reactor’s tungsten walls into the plasma. Fewer impurities mean less unwanted cooling and radiation, allowing stability at higher densities.

Achieved State: This controlled process enabled access to a theorized “density-free regime,” where plasma stability becomes decoupled from increasing density.

Supporting Entities and Parallel Developments

ITER Collaboration: EAST’s findings directly inform the development of ITER, where China is a key partner. Success in extending density limits could influence ITER’s operational strategy and performance.

Next-Generation Engineering (CRAFT): Alongside EAST experiments, China is developing the Comprehensive Research Facility for Fusion Technology (CRAFT). This includes prototyping critical subsystems like a massive vacuum chamber and a high-heat-load divertor, essential for handling exhaust heat in a future power plant.

Global Context: While EAST’s breach is significant, other devices like the DIII-D tokamak in the U.S. have also explored beyond the Greenwald limit, indicating a global shift in understanding this barrier.

Why This Engineering Breakthrough Matters

Power Output Scaling: Fusion power output scales with the square of the plasma density. Doubling the stable operating density could potentially quadruple the potential power output, a fundamental lever for economic viability.

Design Implications: It suggests future commercial fusion reactors might be built smaller and more cost-effectively than previously assumed, as they may not need to be as large to achieve sufficient plasma density for ignition.

Pathway, Not Panacea: This is a major step in solving one of many intertwined challenges. It improves confidence in engineering models but does not immediately shorten the decades-long timeline to a working power plant.

Current Performance Benchmarks and Records

Temperature: EAST has achieved plasma temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius, far hotter than the Sun’s core.

Confinement Time: The reactor holds the record for sustaining high-confinement (H-mode) plasma, achieving a 1,066-second (nearly 18-minute) pulse in 2025.

Primary Goal Remains: Despite these records, no tokamak, including EAST, has achieved fusion ignition—where the reaction becomes self-sustaining and produces net energy gain.

The Material Science Frontier

Divertor Challenge: Managing the intense heat and particle flux is a parallel hurdle. The CRAFT project’s new divertor prototype is designed to handle a steady-state thermal load of 20 megawatts per square meter, a world-leading benchmark for such a component.

Material Innovations: This divertor uses advanced tungsten materials and coatings to withstand temperatures below recrystallization thresholds, showcasing essential progress in plasma-facing component technology.

Direct Answer to a Critical Reader Question

If the density limit is broken, what is the next major obstacle for fusion?

The next immediate obstacle is integrating this high-density operation with the other two pillars of the “fusion triple product”: achieving it at the required extremely high temperatures (over 100 million °C) and maintaining it under high-confinement conditions for even longer durations to demonstrate net energy gain.

Practical Implications and Forward-Looking Perspective

The EAST program demonstrates that fusion development is transitioning from pure plasma physics to advanced systems engineering. Breaking the Greenwald limit redefines a key parameter in reactor design equations, offering future engineers more flexibility. The concurrent development of CRAFT’s engineering subsystems indicates a mature, dual-track strategy: advancing plasma science while solving the formidable materials and engineering problems required for a durable power plant. The path forward involves applying these new operational regimes in larger devices like ITER and iterating on component designs that can survive in a practical fusion environment for decades.

Conclusion

China’s EAST “Artificial Sun” has moved beyond setting incremental duration records to fundamentally re-engineering a core operational limit of fusion plasma. This achievement exemplifies how persistent engineering challenges in fusion are being systematically deconstructed and solved. The program’s integrated approach—coupling groundbreaking plasma science with parallel, large-scale engineering prototyping—provides a robust model for the global pursuit of fusion energy. For industry professionals and observers, the key insight is that fusion development is increasingly a predictable engineering endeavor, where specific barriers are identified and overcome, steadily de-risking the path to a transformative clean energy source.

FAQs

What is the main purpose of China’s EAST reactor?

EAST is a research tokamak designed to test technologies and advance plasma science for the international ITER project and future fusion power plants, not to generate electricity for the grid.

How does breaching the Greenwald limit bring us closer to fusion energy?

It allows for higher plasma densities, which exponentially increase potential fusion power output. This could lead to more powerful, compact, and economically viable reactor designs.

When will fusion energy from devices like EAST be available?

Fusion remains experimental. While progress is accelerating, large-scale demonstration plants like ITER are not scheduled for full operation until the late 2030s, with commercial power likely decades further.