Introduction

Neural Interfaces (Brain‑Computer Interfaces, BCIs) are systems linking the brain’s electrical signals to external devices, allowing thought control for computers, prosthetics, or communication. These technologies bypass traditional neuromuscular pathways to help restore function after paralysis or injury, using noninvasive scalp sensors like EEG or surgically implanted electrodes to decode neural activity into device commands. Neural Interfaces (Brain‑Computer Interfaces, BCIs) are revolutionizing human‑machine interaction by enabling direct neural control and sensory feedback in ways previously confined to science fiction. From medical rehabilitation to cognitive augmentation, Neural Interfaces (Brain‑Computer Interfaces, BCIs) represent a core frontier in neuroengineering with profound clinical and societal implications.

How Neural Interfaces Work

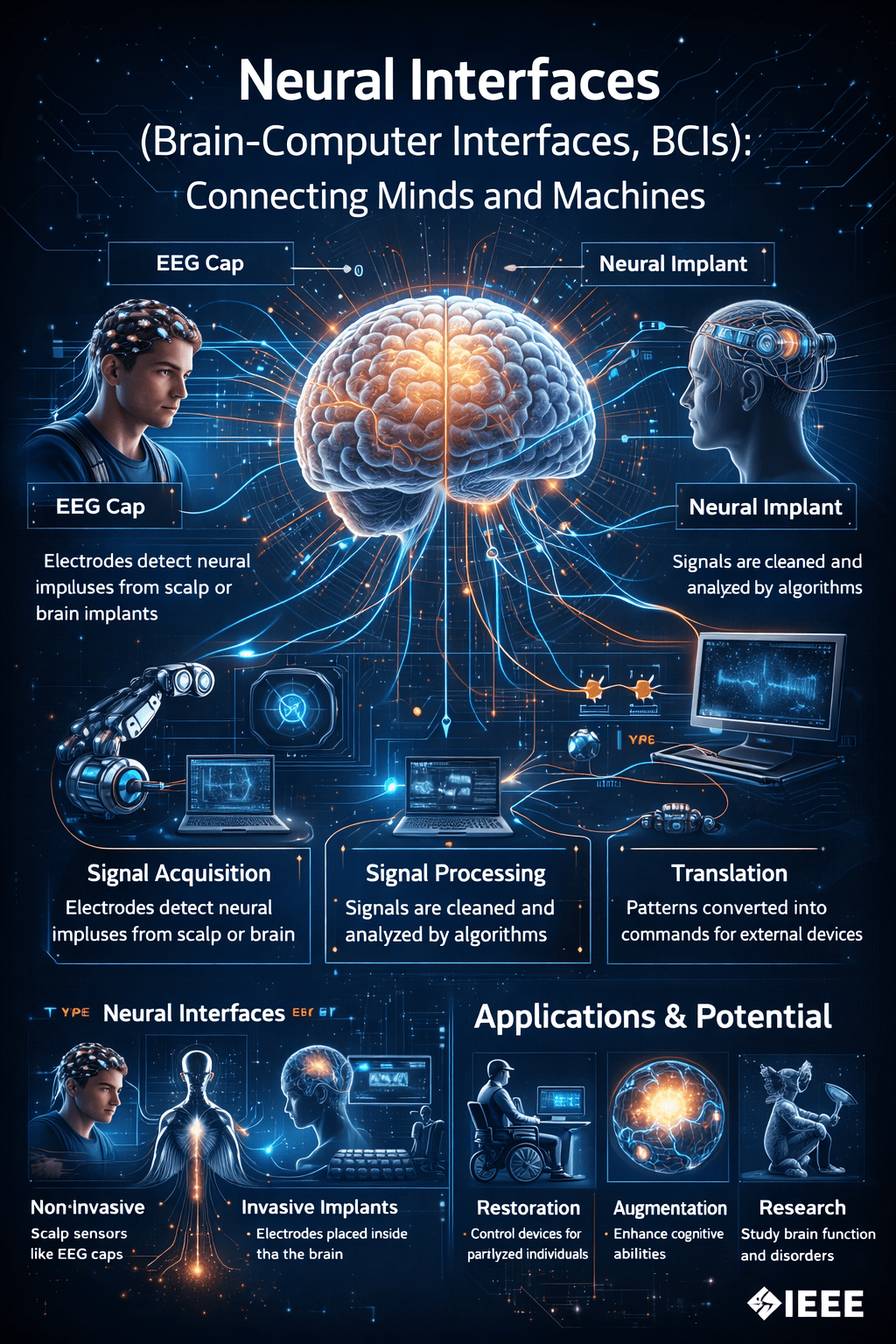

Signal Acquisition

Neural interfaces begin by capturing electrical impulses emitted by neurons. Sensors may be:

- Non‑Invasive (e.g., EEG caps on the scalp) that detect collective brain activity with minimal risk, though with lower signal precision.

- Invasive implants such as microelectrode arrays placed within the cortex to obtain high‑resolution neural signals.

- Semi-invasive methods like electrocorticography (ECoG) or endovascular arrays (e.g., stentrodes) that balance signal quality with safety.

Signal Processing

Captured signals undergo preprocessing—filtering noise and artifacts—followed by feature extraction that isolates patterns linked to intent or motor imagery. Advanced algorithms translate these patterns into actionable commands through machine learning and deep learning techniques, enabling real‑time control of external systems.

Translation and Feedback

Once decoded, neural activity is mapped to device control (e.g., a cursor, prosthetic limb, or wheelchair). Cutting‑edge systems also provide sensory feedback, closing the loop by delivering information back to the nervous system, thus enabling more natural interaction.

Types of Neural Interfaces

Non-Invasive BCIs

These use external sensors like EEG, MEG, or fNIRS to record neural activity without surgery. They are safer and widely used for research, accessibility tools, and consumer neurotech applications, though they trade precision for convenience.

Semi-Invasive BCIs

Semi‑invasive approaches such as ECoG or stent‑mounted electrodes offer better spatial resolution than surface sensors while reducing the risk of open brain surgery. These are increasingly studied for rehabilitative and clinical use.

Invasive BCIs

Implanted directly into brain tissue, invasive interfaces like intracortical arrays provide high‑fidelity signals necessary for precise control of prosthetics or communication devices, particularly for patients with severe motor impairment.

Core Applications and Impact

Restorative Medicine

Neural interfaces are transforming care for individuals with paralysis, spinal cord injury, and neurodegenerative conditions. By translating neural intent into digital commands, patients can control wheelchairs, robotic limbs, or communication interfaces, enhancing independence and quality of life.

Augmentation and Cognitive Enhancement

Beyond restoration, research explores how BCIs may augment human capabilities—from improving memory recall to enhancing sensory perception. As AI and neural decoding algorithms evolve, BCIs could support advanced interaction with digital environments and information systems.

Neuroscience Research

Neural interfaces provide unparalleled insight into brain function, enabling scientists to map neural networks, understand disorders, and refine therapeutic strategies. This drives progress in treatments for epilepsy, Parkinson’s, depression, and more.

Technical and Ethical Challenges

Engineering Barriers

Challenges include achieving long‑term signal stability, minimizing invasiveness, and balancing resolution with safety. External noise, tissue response, and signal degradation remain persistent obstacles requiring continued materials and algorithmic innovation.

Privacy and Autonomy

BCIs raise sensitive ethical concerns about privacy, data security, and cognitive autonomy. Neural data can reveal intentions or emotional states, necessitating robust safeguards to prevent misuse by corporations or malicious actors.

Accessibility and Equity

Ensuring equitable access to BCI technologies is key, as early applications may be cost‑prohibitive. Clear regulatory frameworks and ethical oversight help balance innovation with societal fairness and human rights.

Future Directions

The long‑term vision for neural interfaces spans enhanced telepresence, shared cognition, and seamless human‑AI integration. As BCIs combine with AI and immersive technologies like virtual reality and adaptive assistive systems, they may redefine communication, labour, and even collective human experience. Realizing these goals will depend on interdisciplinary collaboration and ethical stewardship across engineering, medicine, policy, and society.

Recommendation

Healthcare providers and technology developers should prioritize safety, ethical practices, and privacy protections when advancing neural interface systems. Adopt open data and consent protocols, develop standardized clinical pathways, and engage diverse stakeholders in design and deployment. Invest in hybrid signal processing models that improve performance while minimizing invasiveness, and ensure equitable access to BCI innovations across socio‑economic groups.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a brain‑computer interface (BCI)?

A system that translates brain activity into commands for external devices, enabling communication or control without muscle movement.

Are all BCIs invasive?

No—BCIs range from noninvasive (EEG) to semi-invasive (ECoG/stentrode) to fully invasive implants.

What can BCIs be used for today?

Current uses include medical rehabilitation, prosthetic control, communication tools, and research into brain function.